Editor‚Äôs Note: Since we conducted this research project in March 2007, some key points have changed. This is not uncommon in the world of adware. Zango recently filed for bankruptcy and parts of their business have already been sold by the creditors. While ‚ÄúZango‚ÄĚ continues to exist at this point in time, their installation and advertiser base no longer exist to the degree as stated in the following report.

Even prior to what appears to be the demise of Zango, we had noted an improvement

Introduction

We are often asked how big of a role contextual adware applications play in affiliate marketing. Quantitative data can be difficult to come by for numerous reasons. With this case study, we have attempted to put some perspective towards the impact contextual adware advertising in affiliate marketing and on ecommerce.

Contextual adware is a subset of aware (software which generated revenue with various advertising channels). This type of adware displays ads based on the content of the web page an end user is currently viewing. A few of the better known contextual adware applications in operation include Zango, WhenU, DirectCommunications, ContextualChoice, TargetSaver and Vomba. This is not a full complete list.

Many contextual adware companies act as an ad network. They allow advertisers to open accounts and run ad campaigns similar to running a pay per click campaign through a Search Engine. Advertisers chose keyword targets, designate a landing URL and bid on campaigns like they would with a PPCSE campaign. The differences between PPCSE campaigns and contextual adware campaigns are significant. Most contextual advertising charge not on a PPC model, but a CPV (cost per view) model. CPV with contextual adware is really a cost per pop-up model. The keyword targets are often times the domains and URLs of other web sites. The campaigns are not shown on web sites which have consented to display the ads and are compensated when the ad is clicked. Instead, the Advertisers campaign is delivered as a pop-up through an adware application which is installed on the end user’s computer. The web site which triggers the pop-up (again many times this trigger is their domain or URL) is often times not aware they are having a pop-delivered over their web site and they do not receive any type of compensation for their web site causing an ad delivery. Indeed, they may actually be sustaining financial lose because of the ad delivery via the contextual adware application’s pop-up.

We have attempted to quantitate to some degree the impact that contextual adware advertising has on online retail merchants and the role of affiliate marketing with this type of advertising.

Testing

We obtained our list of merchants for testing by using Internet Retailer’s list of the Top 500 Retail Web Sites. We choose this list since our focus is the impact for online retailers. Additionally, the use of an independent list removes the potential bias in results if we were to generate the test list ourselves. Internet Retailer’s list contained some entries for a parent company with multiple online retail presences. In these cases, we included all retail web properties controlled by the parent company in our testing. We did not test the corporate domains, but rather only the domains which conduct actual online retail business. This resulted in a total of 785 domains tested. This provided a fairly large sample size.

While many contextual adware applications are in existence, we conducted our tests with Zango (formerly 180Solutions). Zango is probably one of the best known, and talked about, contextual adware applications. Although total installation base (number of end users with Zango installed) is not truly known, Zango is reporting (see About Zango at end of press release) 20,000,000 users and 200,000 new installations per day.

We performed testing on our Zango test environment. We did this to be certain that Zango was the only adware application operating during our testing. We recorded video of our computer’s desktop and recorded a network log during the tests. For the non-techies, a network log is a recording of all information/data being transmitted over our computer’s network. Our primary interest for this study was all information transmitted over our Internet connection. Review of these logs allowed us to verify ads did originate from Zango, the actual Ad URL placed with Zango for each pop-up we received, any automatic redirects to other web sites that may have occurred and other helpful information in compiling our results. We recorded all network activity during our testing, not just capturing of HTTP header information.

We tested by going to the home page each domain on our testing list. As such, our data is reflective only of pop-ups which were triggered by the merchant’s home page. Other areas of the merchant’s web site could possibly trigger a pop-up, such as their shopping cart page. The testing of additional areas of the merchant’s web site went beyond the scope of this study, but maybe will we look at such things as the targeting of shopping carts for a future study. Once we tested the home page of all merchants on our list (a total of 785 tests), we then retested a select number of merchant who did not receive a pop-up during our initial run.

We did this because we realize that there are many factors which influence whether or not a pop-up is delivered by Zango, even if there is an active campaign with Zango targeting a domain. Some of those factors include if the advertiser is geo-targeting or day-parting their campaigns, ad spending caps with the campaign, how many times the end user has already received an ad from the advertiser and how long ago, how long since the end user last received an ad from Zango and how many advertisers are bidding on a particular keyword trigger. If an ad is delivered and which ad is delivered is a rather complex algorithm. With those considerations in mind, we did one more test run on those domains we suspected (from data review) were actively being targeted for an ad through Zango. In total, we performed 1070 separate tests of the 785 domains of retail merchants.

We conducted our tests over a time period of March 18, 2007 through March 31, 2007. We then manually reviewed all network logs captured during our tests to compile the following results of our testing. All reporting based on the number of domains tested rather than the number of tests performed.

We maintain all documentation on file.

Results

Pop-ups Delivered

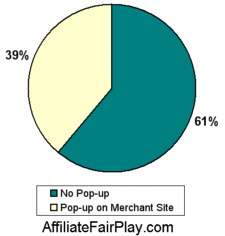

The first set of data points we assessed is how many Merchant’s domains received pop-ups from Zango.

Of the 785 domains tested, we documented a total of 306 pop-ups delivered by Zango. This is 39% of the domains we tested.

It is important to realize that this is the minimum number of merchants tested who are being targeted for pop-up delivery. Because there are many determining factors as to whether a pop-up will occur at any given occurrence of a web page loading in the browser, our results do not mean that only 39% of the domains in our testing were being targeted. If we had continued testing, we may have received additional pop-ups. Indeed, we had numerous incidents of domains triggering the keyword database stored on our computer, which resulted in a call being sent to Zango servers to check for an ad delivery. For whatever reasons, a pop-up ad was not displayed.

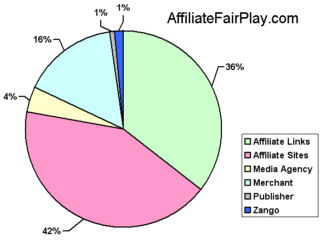

Next we wanted to know, from our sampling, what were the sources for the ads being run through Zango. Who is placing the actual ad, or running the campaign, through Zango.

We determined the ad source by reviewing our network logs recorded during our testing and looking at the actual Ad URL placed with Zango. We classified the ad source into six categories:

- Affiliate links are ads where the Ad URL was actually an affiliate tracking link (e.g. www.network.com. We included both network and in-house affiliate links in this category. We will discuss this more in depth later in this report.

- Affiliate Sites are ads where the domain in the Ad URL was for an affiliate web site  (e.g. www.affiliatesite.com).

- Media Agency are links where the domain in the Ad URL was an advertising or marketing company. Merchant are ads where the Ad URL went directly to the merchant’s web site without any indication that a third party was involved in the ad stream (i.e. an affiliate or media agency).

- Publisher are ads that directed to a web site where the owner is a publisher vs. an affiliate. These sites displayed content pages with PPCSE listings for monetization.

- The final category, Zango, are ads which directed to web sites owned by Zango themselves.

We found the number one source of ads, 42% or 129 pop-ups, to be affiliates using their own domain as the Ad URL. The second largest source for ads, 36% or 109 pop-ups, were affiliates using their affiliate tracking links directly as the URL to be displayed through Zango. The third most common source for ads, 16% or 48 pop-ups, were placed directly by Merchants.

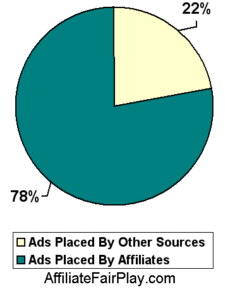

In our testing sample, it is obvious that affiliates are responsible for an overwhelming amount of the pop-ups delivered by Zango. They were responsible for 78%, or 238, of the pop-ups we received during our tests.

This is a significant degree to which affiliates are utilizing Zango to drive traffic. Affiliates are also contributing to Zango’s financial success in no smaller degree.

We should also note that we documented numerous different affiliates responsible for using Zango in our testing.

Since basically any affiliate who is willing to do so can open an advertiser account with a third party contextual adware company, this presents unique challenges for compliance teams. While many networks and merchant preclude such practices in their Terms of Service, it would seem apparent that the industry has yet to adequately address their detection, monitoring and enforcement policies.

In 129 pop-ups where the affiliate used their affiliate link as the Ad URL with Zango, this automatically resulted in a forced click.

A forced click is when an affiliate link is not physically clicked on by the end user, but is automatically invoked. When an affiliate uses their affiliate link as the Ad URL with Zango, that link is loaded into the pop-up window. Tracking of an affiliate click then happens as if an end user had clicked the link. In performance-based marketing, forced clicks are generally considered unacceptable behavior.

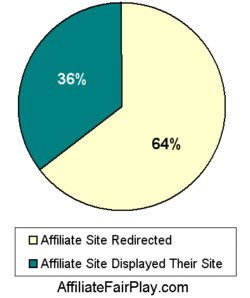

But what happened in the instances where the actual affiliate’s web site was used as the Ad URL?  In 64% of the cases (83 pop-ups), the web page used in the Ad URL was a page which automatically redirected their affiliate link. Therefore, a forced click still occurred. In 36% of those cases (46 pop-ups), the affiliate’s web site itself was displayed without any further activity.

Even when the affiliate’s web site is displayed, this could draw traffic away from the merchant’s web site to a competitor. The merchant may or may not also be partnered with the affiliate. If the merchant is partnered with the affiliate, the end user could possibly click on an affiliate link for the merchant, thus earning a commission for an end user who was already on the merchant’s site.

In any instance where a forced click occurred, the affiliate will again earn a commission for an end user who was already on the merchant‚Äôs web site. If the end user had previously visited the merchant via another affiliate, the forced click would overwrite the tracking of the previous affiliate. If the end user had arrived to the merchant‚Äôs web site from a paid advertising campaign (e.g. PPCSE listing, email campaign, shopping comparison listing, etc), then the merchant could end up paying the affiliate commission as well as their other advertising costs for the same end user. The affiliate forced clicks delivered through Zango would appear to be the ‚Äúlast click in‚ÄĚ and may likely be assessed as the channel responsible for the sale. Obviously, this is not the case.

Forced clicks delivered through contextual advertising adware applications obviously bring no value to the merchant and can be problematic in the affiliate channel. They are indeed considered by some within the Industry to be fraud.

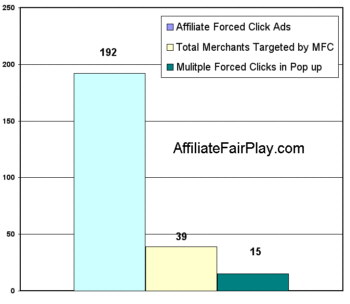

When we looked more closely at the ads displayed in our testing which resulted in a forced click of an affiliate link, we found that a total of 192 pop-ups resulted in forced clicks. This represented 63% of all pop-ups delivered in our test.

Some affiliates using third party contextual adware advertising are not content to automatically set their affiliate tracking for one merchant for each pop-up delivery. They will set multiple affiliate links through one pop-up. They will employ various programming tactics so that one web site is shown in the pop-up. However, any number of other merchant’s web sites (via their affiliate link) are called in such a way that the end user can not actually see the merchant’s site. This practice is called hidden forced clicks. In our testing, we found 15 incidents where hidden forced clicks were used with the Zango pop-up. In those 15 pop-ups, a total of 39 affiliate tracking links were automatically invoked.

This brings us to our next set of data points. Which Networks did we see most frequently in our testing? Our findings may be surprising to many who focus on retail affiliate marketing. In tabulating these results, we counted each occurrence of a link tracking through a Network. For instance, if one pop-up generated three forced clicks through three separate networks, we counted each network involved once. If one pop-up generated three forced clicks for the same network, we counted the one network once. We were looking at how many times a Network was involved in an ad delivery through Zango. We counted only those instances where actual tracking of an affiliate link occurred. The category ‚ÄúOther‚ÄĚ represents all Networks who showed three times or less in our testing.

| Rank | Network | % Of Total  |  # Of Occurrances |

|  1 | Performics | 17% | 45 |

|  2 | Commission Junction |  14% |  38 |

|  3 | Other |  14% |  35 |

|  4 | Linkshare |  11% |  27 |

|  5 | In-house Program |  7% |  19 |

|  6 | Clickbooth |  7% |  17 |

|  7 | ActiveResponseGroup |  6% |  15 |

|  8 | Hydra Network |  5% |  14 |

|  9 | The Useful Network |  5% |  12 |

| 10 | VCMedia/WebSponsors | 2% | 5 |

| 11 | eMarketeMakers | 2% | 5 |

| 12 | ClixGalore | 2% | 5 |

| 13 | 123dmc | 2% | 5 |

| 14 | InnerConcepts | 2% | 5 |

| 15 | SilverCarrot | 2% | 4 |

| 16 | SoftwareOnline | 2% | 4 |

Networks Under ‚ÄúOther‚ÄĚ Category

| AdRevolver | NetBlue |

|  AdTeractive |  NeverBlue |

|  AffilaiteFuel |  RevenueGateway |

| Axill | RewardsGateway |

| BlinkAccess | RocketProfit |

| CardTrax | Rowise |

| Clickxchange | SendTrec |

| COPEAC | Shareasale |

| CPAEmpire | SwishMarketing |

| LeadClick/eAdvertising | TrafficVentureDirect |

| LeadGenNetwork | Traffix |

| Mediashaperz.com/AER Investments Corp | VayanPays |

| MemberSourceMedia |

A total of 42 Networks were involved in the 192 pop-ups involving forced clicks documented in our tests. While many may have expected to see primarily the major traditional Networks show in our study as we were testing primarily mainstream retail merchants, we can see that this is not the case at all. we found that Network involvement was spread out over a wide range of Networks, ranging from traditional Networks to CPA Networks to Media Networks to Gratis-type Networks.

With advances in web technologies, ad syndication has become very popular in online advertising in general. This holds true for Affiliate Networks as well. There are definite benefits of ad syndications nor is there anything ‚Äúwrong‚ÄĚ with such syndication. There is an inherent downside with ad syndication, a diminished transparency in the ad delivery stream. This is significant in relation to quality control and enforcement of TOS.

The ad stream for a syndicated ad looks something like this:

publisher -> network1 -> network2 -> network3 -> advertiser

Each network automatically redirects to the Network above them until the final the network, which the advertiser has an account, is reached. This final network then displays the advertiser’s ad. In affiliate marketing, it becomes affiliate URL’s which are being automatically redirected between networks. Each entity (publisher and networks) would then receive some degree of compensation when a commission is earned.

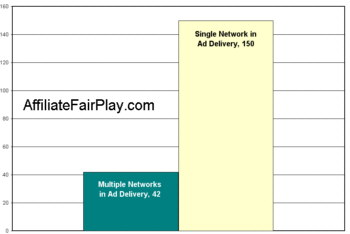

In our testing results, we found that were a total of 42 instances (22%) of ad syndication involved where forced clicks of affiliate links occurred.In this testing study, we found anywhere from two to four networks involved when syndication was present. The transparency issues with ad syndication can make detection of bad behavior more difficult to identify and police.

Contextual advertising companies often market themselves to consumers as ‚Äúsearch assistants.‚ÄĚ The claim is that they will provide the consumer pop-up ads to other web sites which may be of relevant interest to the consumer, based on the site they are currently visiting. While the whole concept of using adware to pop-up competing web sites is a controversial practice itself, we looked at whether or not the pop-ups being delivered did indeed deliver to the end user as promised.

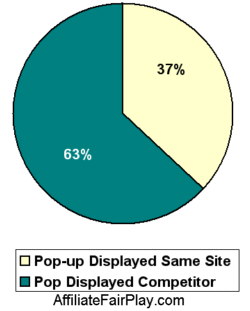

In our testing, we found that in 193 pop-ups (63%) a competing web site was displayed. In 113 pop-ups (37%), the same web site that end user was currently visiting was displayed. There is no ‚Äúsearch‚ÄĚ value to the end user when presented with a pop-up of a web site they are currently visiting. Indeed there is little or no value to anyone except the affiliate using the adware to elicit a forced click for that merchant and the adware company charging for the pop-up. In a small number of cases (8 pop-ups), we found that the merchant themselves popped their own site over their site.

But even the cases of competing web sites in the pop-up were not always clear cut as they would seem to the naked eye. There were times that the competing merchant in the pop-up was placed by an affiliate, not the merchant themselves. Other times, a competing merchant was seen in the pop-up, but a hidden forced click for the merchant popped on occurred. So while it ‚Äúlooked‚ÄĚ like a competing merchant (or affiliate of a competing merchant) was targeting a merchant, they were in reality being targeted from within their own affiliate program as well.

A competing web site was not always another merchant in the same vertical/niche. The 46 pop-ups which were an affiliate web site were counted as a competing site. These sites were competing in the since they could possibly draw traffic away from the merchant’s site to another merchant. We also documented 46 pop-ups (15%) which were gratis/incent marketing offers.

Gratis Marketing

Gratis or incent marketing is a marketing approach where consumers can ‚Äúearn‚ÄĚ a free product by performing certain prescribed actions. These usually include registering, subscribing or joining a specific number of services/offers. These are the win a free iPod, gift card, plasma TV, etc offers. Gratis promotions are typically associated with CPA Networks and many in affiliate marketing consider them very separate from traditional, retail merchant affiliate marketing. It is considered segregated with little direct impact on traditional affiliate marketing efforts.

The impact of gratis marketing on traditional retail affiliate marketing should probably not be discounted so quickly however. Although our testing domains were comprised of the top 500 Internet Retailers, considered aligned with traditional affiliate networks, fifteen percent of the pop-ups we received were for gratis type offers. This is not an insignificant number of pop-ups in our opinion. Consumers do participate in these types of promotions, controversial or not. There are several major companies who specialize in this type of promotion and these companies are quite successful. Major brands ‚Äúsponsor‚ÄĚ these types of promotions because they can deliver high volume. This can happen only if consumers are indeed participating in the offers. It is obvious that the high volume is, at least in part, being delivered through adware advertising. Common sense would seem to dictate that if a consumer goes to MerchantX.com and then immediately receives and ad telling them they can get a free $500 Gift Card for MerchantX, there is a certain percentage of consumers who will be enticed by the offer.

CPA Networks

The prevalence of CPA Networks showing in our report is related, in a large part, to ads for gratis promotions. We did document instances where a forced click occurred for a retail merchant through a CPA Network instead of a traditional affiliate marketing network. In one instance, we received a pop-up for ThompsonCigar via a HydraNetwork affiliate link when we went to ThompsonCigar. ThompsonCigar’s main affiliate program is on Linkshare. In another instance we recorded a forced click for 4inkjets via a HydraNetwork. 4inkjets runs their primary affiliate program through CJ. In yet another instance, we documented a forced click for Perfume.com which went through two CPA Networks, AdTeractive and Clickbooth. Perfume.com runs their primary affiliate programs through ShareASale and an in-house program. We documented other such instances during this test. While a majority of offers on CPA Networks continue to be lead gen type offers, there are an increasing number of retail merchants who have promotions through CPA Networks.

Conclusions

We encourage readers to keep in mind that we tested only one contextual advertising adware application. There are several other such applications in existence. Additionally, there are several Ad Networks which act as aggregators for adware companies. They accept campaigns from advertisers and then provide these listings to numerous adware applications. As such, the impact of contextual adware advertising on affiliate marketing and merchants is broader than the specific numbers reported in this study.

It is the opinion of AffiliateFairPlay that a minimum 39% incidence of pop-ups by an contextual adware application towards the top internet retail web sites is a significant figure that can not and should not be ignored. There is no way to avoid the fact that some degree of negative financial impact is being incurred by merchants who are having such activity targeted at their sites. Online merchants should be afforded the same rights and protection to conduct competitive but fair trade without undue interference which is afforded to brick and mortar retailers. When fair competition is absent, then consumer ultimately loses.

We find it completely unacceptable that 78% of the pop-ups delivered on the top 500 Internet Retailers were associated with affiliate marketing. Such a high degree of activity can not be healthy for the Affiliate Marketing Industry as a whole.

AFP is aware that many networks and merchants do not approve of forced clicks through adware. We also acknowledge that there are certain networks and merchants/advertisers who not only approve but encourage the practice. For those who do disapprove of the practice, it would seem that as an Industry we have yet to implement and act upon appropriate mechanisms for controlling such behavior.

It is obviously not enough to just say that a practice is unacceptable. We do not feel, given the information presented in this report, that our Industry can be apathetic towards the issues and impact. AFP tests for this type of behavior frequently. We appreciate the challenges associated with detecting affiliates using third party contextual advertising. However, networks and merchants should be actively pursuing such activity by their affiliates and acting upon the occurrences swiftly and decisively. As an Industry, it is our responsibility to protect the integrity of our businesses and livelihoods. All members of this Industry, from networks to affiliates, should expect and demand a certain standard in delivering performance-based marketing. Practices and behaviors which diminish the overall value of affiliate marketing should receive a zero-tolerance from the majority within the Affiliate Marketing Industry.

If AFP performs a similar study again in six months, what will we find? Will we find less, more or no change in the degree of affiliate marketing related to contextual adware advertising?

Pingback: Contextual Adware Advertising Impact Study Released